Things we learnt trying, and failing, to build a regulated social savings service called Savemates

In a similar manner to how Listerly began, Savemates started with a conversation between myself and Paul about an idea that we’d both arrived at independently - the potential to digitise an ancient form of group savings called a Rotating Saving and Credit Association (ROSCA).

I’d been interested in this idea from my time working at Sidekick Studios, when Adil had come up with a way to implement the model with a charity via a programme we were running called Sidekick School. Paul had stumbled into the concept on his travels round the internet, and when he bought it up with me it reminded me of the Sidekick project.

What is a ROSCA?

A ROSCA is a very old concept that predates formal banking and makes it possible for unbanked people to save money together. The idea is pretty simple:

- You get a group of people who trust each other together (lets say its ten friends)

- Everyone commits to save the same amount every month/week/whatever (lets say £100)

- At a point during the month, everyone pays into a ‘pot’ of some sort

- One person in the group then gets the whole pot (£1000)

- This is repeated over ten months (because there are ten friends) until everyone has had their payout from the pot

A ROSCA is basically a mix between a saving and a lending solution - depending on where you are in the cycle you are either lending or borrowing from the people in the group. The whole thing hangs together based on trust between the members of the group.

ROSCAs are run all round the world in most countries. They have a wide variety of names (Chit funds, Syndicate, The Partner, Committee) and are typically run by poorer people as a way to get round the problem of not having access to credit. They also ensure financial discipline. Some middle class groups in richer countries still use the mechanic, but invest the ‘pot’ systematically in more advanced financial products like stocks and shares.

What about a digital ROSCA?

At first glance, this seemed like a dream opportunity for digitisation, and a perfect fit with our vision for Makeshift. At first glance a digital ROSCA product has all sorts of amazing characteristics:

- It feels inherently ‘viral’ in that you have to ask your friends to join to make it work

- It appears to make money from the first customer, as it involves large amount of money being moved around

- It seems very sticky - once a group signs up they use the service for many months

- It’s built on an existing behaviour in the real world, so it feels like we’re not inventing a new kind of thing, just moving it online

- It fits perfectly with our ‘giving a leg up to the little guy’ proposition because its helping people become more financially independent without help from the big evil banks

- The market felt ready for this - banker bashing was at an all time high, everyone in the government, the media and the industry was talking about the need for new models

- Finally, it will be fun to build because it’s obviously a hard thing to do

It seemed too good to be true to be honest, and, as you’ll see it was. Anyway, we were pumped up and full of ambition. The company had been running for a few months and we were feeling optimistic.

So we started doing some desk research into the space and got back a strange result - no one had really had a go at digitising ROSCAs. We did find a few tiny projects that looked like they’d never really got off the ground, but overall this made us more confident (it shouldn’t have) that we were geniuses for spotting this hidden gem.

The next step was to do what we always do and try and build a tiny prototype or hack as quickly as possible so we can go and have some conversations with potential customers that involve them interacting with a real ‘thing’ instead of responding to questions.

The hack

Stef had recently met a great coder called Tanja (who we later managed to hire full time) and we asked her to come down from Edinburgh to work on this project and help us build an MVP in a week.

Tanja flew down, and after a pretty insane half day briefing over wireframes and coffee she went back to Scotland and coded the shit out of it for four days with a bit of copy writing and visual design support from me.

Above: UI designs for the hack

At the same time we decided that the ROSCA concept would really benefit from a film treatment to show how the money moves around over time, so we hooked up with a guy called Adam who cranked out a lovely little animation for us in a few days.

The first big mistake

So we were one week in, and we had a nice little app that explained the concept, let you create a group, set a monthly saving amount, invite your mates via adding their emails, and then ‘activate’ your group once everyone had joined. At this point we just displayed a message saying ‘thanks you’re in the queue’ or whatever.

So far so Lean Startup. We had the classic MVP to test the proposition with, and we began doing user testing sessions with people we thought might like the proposition (low-medium paid white collar). The feedback from the small number of people we got was good - we had one person from a Pakistani background say ‘oh my god, this is just like the thing I do with my mates called Committee, but online. I’d totally do it!’ The anecdata was looking good.

But this is where we made our first really big mistake on the project. Instead of just ‘launching’ it via PSFK, Springwise and those other kind of ‘here’s a cool thing click on it’ services and trying to get a lot of eyeballs we started speaking to people with lots of experience in the P2P finance sector, in particular the guys who had setup Zopa, one of the UKs most successful P2P services. One thing led to another and we got introduced to some lawyers … and here all our sorrows started.

We got a nasty surprise after our first meeting with a very experienced lawyer called Simon Dean-Johns, and this was backed up by the second opinion of our general counsel Mike Buckworth. Their view was that Savemates customer offering of a ‘group savings scheme’ constituted some sort of a regulated financial services activity, akin to banking, money transferring or something similar.

They weren’t sure exactly where it should fall in the regulation spectrum, but the overwhelming advice was ‘this needs to be regulated, if you don’t get regulation you are exposing yourself to potential prosecution.’

Shit.

The additional piece of shit is that because we assumed this had to be a regulated business, we couldn’t openly market it to potential customers (aka get feedback from people we don’t know) until we had the stamp of regulatory approval

Shit.

At this point, we had three choices. And looking back on it we made the worst choice of all.

We could have said, we don’t care what you say, we’ll ‘launch’ without regulation. This would have been the best option in hindsight.

We could have thrown in the towel at that point because what the hell did we know about running a regulated financial services business (hint, nothing). This would have been second best.

Or, we could say, fuck it, we’re all in on this, lets get regulated and show those fancy suits that we can do this better than them. We’re changing the world by ‘giving a leg up to the little guy’, right, and finance is the most awful, big guy industry out there. Lets do this!

Oh dear

So, full of self righteousness we began applying for regulation and building a rock solid product that would withstand regulatory scrutiny. This meant conforming to all kinds of security procedures, providing all kinds of legal guarantees, creating a new company, opening new bank accounts and lots and lots of fees for those lawyers.

I should say at this point, that at no point did I feel that the lawyers and other professionals we were working with misled us. They gave us the best advice they could with the information they had, and we were worried about being accused of criminal activity so we followed their advice. But as we’ll see, it was a tragic waste of time and money.

Anyway, the end result was that I ended up writing a document that is pretty much the exact opposite of everything we were trying to do at Makeshift about moving fast, experimenting through making and just getting on with stuff. As part of the regulatory submission I had to produce a five year business plan. For a product with no traction. That we weren’t allowed to test out.

I’ve embedded it below - this is a really epic thing. 33 Pages of beautiful, creative, well argued bullshit. Here’s the link to it on Speakerdeck.

Meanwhile we had the the legal position for Savemates drawn up into a mega lawyer gobblydey gook document, explaining why it didn’t constitute deposit taking (banking) but instead fell under the more lightly regulated area of money transfer.

Back to the app. You did remember we were trying to make a digital product, right?!

So, alongside doing all this speculative business crap we were actually, initially, really enjoying designing the more complete version of Savemates off the back of Tanja’s hack.

We’d asked Tony Daly to come and work with us on Bitsy, but in the time it took for him to agree, we’d gone from ‘we’re all in on Bitsy and need a tech lead’ to ‘we’re killing this’, so when he turned up for work on the first day we said, fancy working on Savemates instead?

Fortunately Tony’s a very easy going guy. So he said yes, and we set to work building a regulation strength financial services app.

As you might imagine, this took a loooong time. The Savemates app is really complex, as we have to separate all sorts of concerns and build multiple apps, comply with all sorts of security measures, ensure the software is very robust by building everything using strict TDD methods - and create a really simple UI that feels solid and reliable to users.

Above: Our ‘Obese Non-Startup’ Technical Architecture

Oh, and we have the small problem that we have to process payments, store money and then transfer it back to people.

The payments bit chewed up vast amounts of our time and energy, as there simply was no ‘best’ solution. The dream for us would have been to have access to the Faster Payments network or BACS via a partnership with a bank, so we could use Direct Debit to transfer the money in and out of our customers accounts.

Using Direct Debit would mean our transaction fees approach zero, and our customers just have to enter a few details (personal stuff + sort code and account number) - but, it would mean another massive layer of scrutiny, and we had to have a bank partner. And we might get accused of ‘holding deposits’ which makes us a bank. Which we don’t want.

I still believe a deep Direct Debit integration is the only way to make this product work and get the margins you need. Anyway.

However, that wasn’t on the cards, as it would take six months to get anywhere near this approval, and the tech challenge was vast. We simply didn’t have the runway to do it.

So instead, we went with a simpler, but flawed idea. We’d use Stripe to process the payments in, and then do manual payouts via our own online banking service with Barclays. This meant our customers had to fill out the most evil form of all time when signing up. They had to give us:

- Their email

- Their full name

- Their date of birth

- Their address

- Their credit card numbers

- Their bank account numbers

Admittedly we could spread this out over several steps, but its still pretty much the mother lode if you want to steal an identity. But we had to request it, because to comply with regulatory stuff we had to ‘know our customer’ and submit this information to a third part ‘know your customer service’ to see if it checks out (sort of like when you have to bring two bills and ID to rent a car).

Oh, and we had to run every name past the Bank of England’s anti-money laundering hit list of known criminals and terrorists. And a bunch of other stuff.

We explore other options like using GoCardless and various other things, but these were dead ends because of various reasons including the UX and Terms of Service issues. Meanwhile we’d setup another company, Savemates Ltd, get a separate bank account that acts like an ESCROW to hold all these funds we’re expecting.

An aside - solving hard problems is fun and distracting

I should say, all the way through this I was really enjoying it. This was one of the hardest things I’d had to design, and I was learning loads. Every time we hit a barrier from the guys in suits I was pumped about overcoming it. But this was a really bad thing, because it basically gave me a constant list of excuses as to why we weren’t shipping and had to do more designing.

Anyway, the end result was that after three months of hard work we were getting pretty close to a functional experience on the back end, but what about the way we present the product, get people to join and generally promote this increasingly expensive beast of a business once we’re allowed to launch it?

Meanwhile, what do customers think? Remember those guys?

So whilst we were messing around with all this tech and legal stuff, we were very aware that we were getting no feedback from customers, so we took the drastic step of commissioning some qualitative research from Jaimes to help us figure out how to position the product in more depth (we had some vision stuff from our business planning exercise).

We started doing some individual interviews and some group sessions about attitudes to savings, and the role of friendship in this.

We spoke to some people who had used cash ROSCAs and spoke to some other people representing our hypothesised user groups - people who take part in community groups on lower incomes (and therefore with more need for alternative sources of credit). This pushed us towards women - our split was around 70 - 30 women to men.

Anyway, we did various exercises to get people to open up about how they think about saving, borrowing and friends. And we learnt a lot. That we should have learnt much, much earlier.

Above: One of our personas created from our research work

Firstly, and I’m obviously generalising, people’s attitude to their personal finances is totally weird and counter intuitive. It (sort of) bears no relationship to how financial institutions want you to think about money, and people lie to you, themselves and each other in group situations when talking about money - which didn’t bode well for our ‘group savings’ product.

What did we learn?

Well, we learnt a lot. But to try and summarise a bit, I’d say that I learnt four main things:

1 People just don’t like to think about money if possible

Counter intuitively, the point of having money is to not think about money - if you have disposable income it means you can just buy stuff without thinking too much, and this is liberating. Even people who run businesses very carefully and count every penny (as I do) don’t like to do this in their personal life.

2 The financial services industry had brainwashed us

On top of the fact that people don’t want to think about money, our product is confusing because it goes against the grain of how the FS industry has educated everyone - to think of all money activity as a binary divide between either saving or borrowing. But we were somewhere in between, and that just freaked people out.

3 Friends and money don’t work very well together

One of the most common questions people would ask about the concept is “what about when one person defaults?” I think this is because people have learnt to be untrustworthy when money is involved, but when you point out it would be their best friend, and if they defaulted it would be because of a really serious reason (like a death, or unemployment), they generally respond with, oh, ok, well I’d let them off.

But this then leads you to the next really deep problem with the Savemates hypothesis in markets that re saturated with credit - people don’t like having any obligations to their real friends about money.

When you think about it, this makes total sense. In some ways, you can see money as solving the problem that we can’t all be friends with everyone. We use money to manage trust issues between strangers. This is a topic addressed brilliantly in David Graeber’s book, Debt, the first 5000 years.

For us, this meant that the Savemates groups had to be totally, utterly fair. So some of our more exotic ideas about offering a sort of bidding system or interest rates within the group were way off the mark. People just wanted to get out what they put in. The ‘shuffle’ mode we were proposing got the best feedback based on it being the fairest system.

Above: The four proposed product types

4 Money is the route to wealth, not the wealth itself

Finally, we realised what all financial services marketeers know - you need to focus on the outcome of having this pot of money - we called it the ‘lump sum’ - that you can use to get a car or something big that you otherwise wouldn’t be able to get.

A final bonus insight - we realised we couldn’t charge any fees. Probably. At least the proposed 2% fee went down badly in the groups, as people felt that at least that you should get back whatever you put in.

Meanwhile the FCA had called us and said we had to adjust our business plan because we can’t invest the money or rely on interest payments to fund the business. So no fees, and no interest payments. And a high transaction cost because we can’t use Direct Debits. And a huge educational cost.

Shit.

Things weren’t looking good.

Back to the app

Ok, so back at our desks we were still furiously coding and designing this beast of an app. It turned out its really an email app. Its working if you aren’t thinking about it or doing anything. But this ran against our view of one of the best features of ROSCAs which is the community bit - meeting up with your mates to share the moment of giving or receiving wealth.

So we decided to make people return to the app, at which point we thought we could try and make some more money out of them with ‘deals’. After all, we had to make up for all the lost imaginary money the FCA, the technical barriers and our consumer research had stolen from us right?

At this point we really started to see why banks are big, and why they have evolved from the simple form of a ROSCA.

Anyway, the whole thing was heading for the ropes, and we’d spent a lot of money - around £75,000 by this point, in part because we were running the whole project on freelance resource. Tony didn’t want to join us full time, so he was on a day rate, and we got Chris Waring back to do UI work on the product.

Despite having a great team, the flows were just so epic. The whole customer journey takes many months to complete.

Above: The ‘core journeys’ for Savemates. Yeah. Insane.

We were drowning in scale, and getting disheartened because it had been so long without good news, let alone customer feedback. And because it was being built by freelances it felt disconnected to the progress we were making with Hire my Friend, Help me Write, Wrangler and Attending.

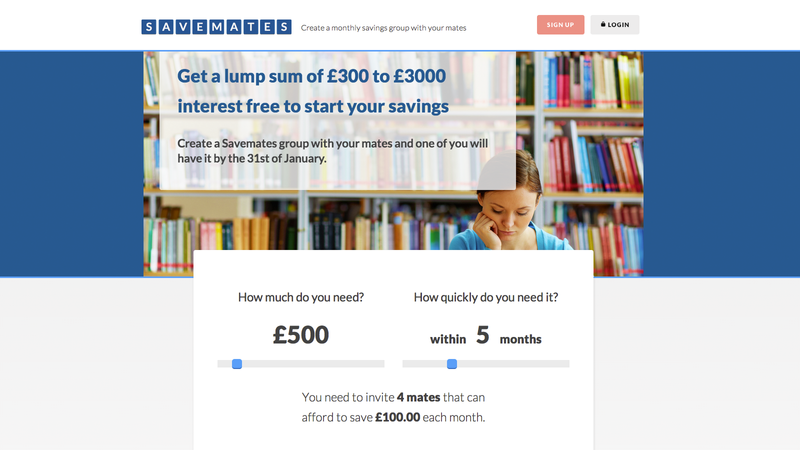

Anyway, we pressed ahead and very, very nearly shipped a finished product. We built a lovely marketing site, and very, very nearly nailed the whole group creation, personal details collection, money processing and admin reporting stuff…

Above: Mmmm... marketing site

Meanwhile, back at the ranch

Whilst all this was going on, and part because all this was going for so long, on we had a re-think about our proposition and what we were doing at Makeshift based on the traction we were seeing with Wrangler, Hire my Friend, Attending and the Makeshift brand more generally.

We made some big decisions towards the end of the summer, which were:

- We’d focus our offering down onto ‘tools for startups

- We’d only build things that we could use ourselves from day one

We had previously kept space for non-tool based products with viral growth hypotheses (like Help me Write and Savemates), but we decided to focus even more. So, with that strategic decision Savemates clearly did not fit the bill. It wasn’t a ‘tool for startups’ and the customer really wasn’t us - it was probably poorer people active in faith and community groups who can’t access credit. Which is not us.

So, we just, stopped.

Above: Our new line. No room for ROSCAs here.

In some ways this was really annoying. I love the product idea, I hate banks and the FS industry with a passion now. I think there is a thing here, but weighing it up against the other products it was too complex and too far away from our own experience. I was gutted to have wasted so much time and money on a thing that never really shipped - this was the opposite to why we setup Makeshift.

And so, it sits there, 90% done in every possible way, unused. A monument to why Lean Startup works - because you don’t waste time not shipping - and why it doesn’t work - because you can’t do something this big without a leap of faith in yourself and the market.

I think someone could make the digital ROSCA concept into a business, but I think they need deep experience of consumer finance in the UK and ideally other markets, a team of about five people to start with, and a five year runway to execute. And then they might just have … another bank on their hands!

The icing on the cake

A few months later, after we’d killed it, we finally got a call from the FCA saying ‘we’ve completed your application, and following a diktat from the treasury we’ve decided to ease off on regulation of early stage FS startups … so we don’t believe this class of business needs regulatory oversight.’

My jaw hit the floor. No. Fucking. Way.

All that lawyer nonsense was for … nothing. If we’d known this at the start Savemates might have shipped. Having said that, we had to do all this, to force the FCAs hand to issue a verdict on digital ROSCAs, so that was an impossibility. I think I’m still in denial about this to be honest.

But, hopefully it won’t be in vain, because now we know that if you want to setup a digital ROSCA you should just … do it. Don’t hang about, don’t ask for permission from the masters of the universe - just get out there and get on with it. If only we’d done that.